Measuring daylight to predict the future

It’s late winter in an alpine meadow. For the past few months, the local plants have been waiting out the cold weather, mostly not growing. Usually, this would continue for a while longer because spring doesn’t come for another month or two at this altitude. But this year an unexpected thaw arrives. Temperatures rise to unseasonal levels, snow melts. Plants in the area are faced with a choice: Should they start to grow or continue to wait? To start growing risks getting caught by a return of cold temperatures.

Many alpine and arctic species avoid getting caught in early and temporary thaws by conditioning their growth partly on light. Mountain sorrel, shown below, is one of many plant species capable of this photoperiodism—the ability to condition its activity on Earth’s annual cycles of light and darkness. Mountain sorrel will begin to grow only when the days have become long enough to show that spring has truly arrived, no matter what a given day’s temperature might suggest.

Mountain sorrel growing in Mount Rainier National Park. Photo by Walter Siegmund. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Oxyria_digyna_8596.JPG.

Photoperiodism in plants involves their ability to “measure” the length of daylight (or darkness) during a 24-hour period. For organisms that live for months or years, as many plants do, that is not a surprising skill. But what about organisms with much smaller lifespans, organisms whose entire existence may pass in less than 24 hours?

Helping tiny organisms survive the cold

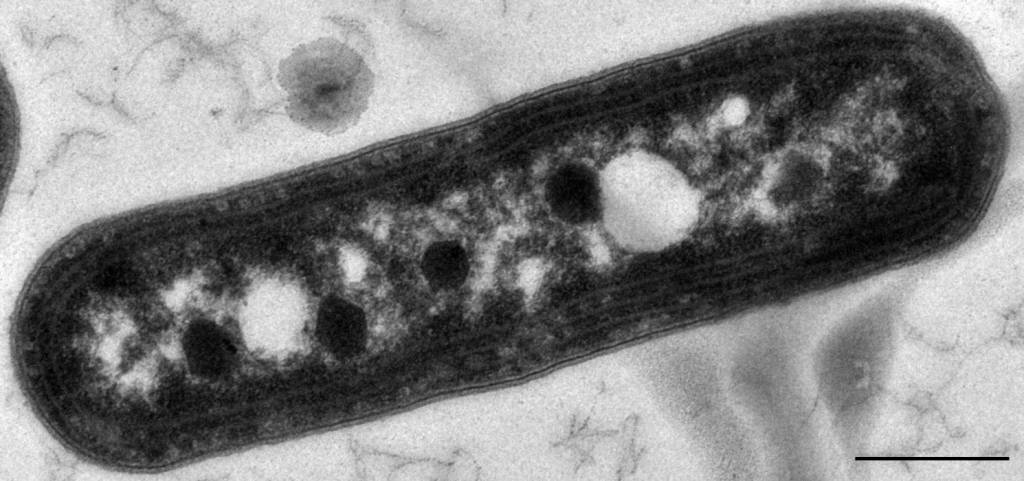

To answer that question, researchers at Vanderbilt University recently looked for photoperiodism in a small aquatic bacterium called Synechococcus elongatus. Just like mountain sorrel, these bacteria make a living through photosynthesis, by converting the sun’s energy into chemical form. Unlike mountain sorrel, they are single celled.

Electron micrograph of Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. By Raul Gonzalez and Cheryl Kerfeld is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. https://www.kerfeldlab.org/images.html.

Microbial photosynthesizers may not be as obvious or widely appreciated as plants, but they actually carry out half of all photosynthesis on earth. They live in a wide range of aquatic settings, and just like plants, are subject to the vagaries of the environment. For this reason, they could benefit from using day length to predict seasonal changes.

The thing is, they don’t live very long, often much less than a day. Such a short lifespan would seem to make it challenging to measure the photoperiod—the length of daylight—accurately.

To find out if Synechococcus responds to changes in day length the Vanderbilt researchers grew them in three different light conditions: a long-day condition (16 hours of light, 8 hours of dark), an “equinox” condition (12 hours of each), and a short-day condition (8 hours of light, 16 hours of dark). Then they tested the survival of the bacteria in freezing cold.

What the researchers found is that those bacteria subjected to shorter periods of daylight survived the cold better. This short-day group had a cold survival rate two to three times higher than the other groups. This suggests that Synechococcus is using short daylight as an indication of the coming of winter. In response it activates various cold-tolerance mechanisms to help it survive.

How the bacteria actually do it

The researchers then tried to identify what specific cold-tolerance mechanisms might be involved. One possibility relates to the molecular composition of the cell’s membranes, which are primarily made up of lipids. One previously known mechanism of cold adaptation is to make the fatty acids within these lipid molecules less saturated. This helps keep the membrane fluid in cold temperatures and is known to happen in a variety of organisms including Synechococcus. When they looked at this, the Vanderbilt team found that indeed, the short-daylight condition makes Synechococcus cells desaturate their membranes even before they’re exposed to cold.

The next question was how such changes could work on the molecular level. The group suspected that photoperiodism in Synechococcus might be connected with the circadian clock. Like many organisms (including humans), Synechococcus cells have a sort of molecular clock that operates on a 24-hour cycle. Among other things, this allows them to anticipate when the sun will be shining. The researchers wondered if this circadian clock might also help Synechococcus measure the length of daylight, and thus anticipate the seasons as well.

Fortunately for the Vanderbilt team, the circadian clock in Synechococcus has been well studied. They used the fact that the bacterium’s clock genes are already known to test if there is a connection to photoperiodism. They repeated their experiments using strains of Synechococcus in which various circadian clock genes had been knocked out (made non-functional). They found that knockout strains exposed to short days do not develop cold adaptation. Disrupting the circadian clock thus prevents a photoperiodic response and strongly suggests that photoperiodism in Synechococcus depends on the clock.

It is not yet known exactly how the circadian clock is connected to mechanisms for measuring daylight or responding to cold conditions. However, knowing the circadian clock is involved gives researchers a sort of molecular foothold on this problem. It seems likely that in the future they will be able to work out the molecular mechanisms underlying photoperiodism in Synechococcus in full detail.

(This article was first published on Medium.)

Leave a comment